As an English major in college, I became disillusioned with how I was expected to write about literature. It seemed to me that you took two texts — what used to be called “books” or “stories” or “passages” or “lines” — and compared them, concluding that they were either different or similar, and used sophistry and rhetoric to show why you were right.

That was criticism, and that, apparently, was the job of the English major. At my college, you could also take classes in literary criticism, in which you applied the same kind of thinking to criticism, thereby doing criticism of criticism.

After learning about those infinite mirrors, I dropped out for a while and spent a lot of time writing about writing: the kind of writing I was or wasn’t doing, the kind of writing I wanted to do, what it meant to be a writer. (Eventually I went back, and dropped out again; sadly, because I received a diploma in the end, I must call myself a college “stopout,” since a dropout has the distinction of never graduating.)

Fast forward more than a quarter of a century, an eyeblink. For many years, I had been a non-practicing writer. I used to torture myself with the question: What do you call a writer who doesn’t write? When I was 15, I had a very clear vision of myself Being a Writer: going to cocktail parties, the toast of the Literary Scene, drinking and dancing and waking up wearing someone else’s sweater and sitting up in bed reaching for my notebook and pen, so hungry to put words on the page that I’d work through the hangover.

Reality, unsurprisingly, looked more like my teaching life: spending all day either talking to students about writing, reading student writing, preparing and delivering “lessons” on writing and reading, and getting far too tired of other people’s words to commit any of my own to the page.

People gave me books as gifts, and I treated them as decorative or weight-bearing elements in my life, moving them from home to home and reorganizing them from shelf to shelf and occasionally culling them for trade at my favorite bookstores, but reading only a few of them.

In the middle of my teaching life, I came to my First Reading Realization: I was asking people to value and participate in the reading life, and most of my reading from age 17 onward was assigned reading, assigned either to me or by me, but never feeling “chosen.” So I decided I was going to read for pleasure, whatever I wanted to read, and I started to keep a log of the books I read. I didn’t include books on tape, which I devoured voraciously when I had a daily ferry commute, so the books I’m familiar with aren’t all represented in my little blue notebook, but every book I’ve picked up and held in my hands and started reading is entered there, with the starting date and either an ending date or an open dash, sometimes with a basic note, like, “Ret’d to libe.”

It’s shocking to me how few pages the titles I’ve read since 1998 fill. Having given up shame, and doing this really only for myself, my only concern is that future historians won’t really understand how such a literate-seeming person could consume such a small amount of literature. (My explanation: I own a lot of books and I’m good at memorizing titles and their authors.)

My Second Reading Realization came a couple years ago, when I gave myself permission NOT to read every copy of The New Yorker that piled up next to my bed. I have long loved the idea of The New Yorker, and for many years had a subscription gifted to me by my sister-in-law. I think a subscription to The New Yorker ideally requires a household with four readers; each person treats The New Yorker as a monthly subscription, reading one out of four issues, sharing their favorite articles and stories with the other three over dinner, and never feeling obliged to keep up.

So I threw away a huge pile of New Yorkers (meaning I recycled them, which is what it means to throw things away in my part of the world. I would get such shit from the Pacific NW puritans if I put them in the garbage can, and as it is, I consider it a sign of mental health and rebellion that I don’t donate them to the library or thrift stores, since often the perfect way of disposing of objects mean they never leave your house and I do not intend to get buried in an avalanche of New Yorkers, read or unread).

Now I have a system: When a new New Yorker comes in the mail, I read it every night before falling asleep, putting aside any other reading matter I happen to have in my possession. This means the books pile up and the other stray magazines that comes into my possession pile up, but New Yorkers, once read, are discarded, and I don’t miss them when they’re gone.

A few years ago I sustained some neck pain. There was no accident or injury, just the discovery of some books I couldn’t stop reading until they hit me in the face as I fell asleep reading in bed. (The Mary Russell books by Laurie King, in case you were wondering.) I learned that I needed a reading-in-bed method that didn’t put quite so much pressure on my spine, so now I read on my side, with a special pillow (known as Mini Trewn, the successor to the original Trewn, a body pillow, and companion to Trewn Junior, who sleeps between my knees to keep my spine aligned and my bones from grinding irritatingly together).

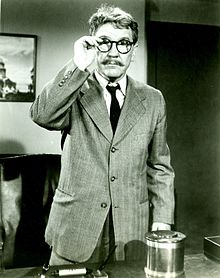

(“Special,” by the way, is one of my husband’s designations for “things other people seem to need to get by when all I really need is a book and sufficient light to read by,” kind of like the Twilight Zone’s Mr. Bemis.)

The Third Reading Realization is actually a Writing Realization : Now that I am reading whatever I want for whatever reasons of taste or self-discovery or convenience or guilt I bring to the page, I’m ready to write. Every day. Like this. Not a number of pages or a number of hours, not in a specific place with a special pen, but in words and sentences I’d like to read, and enjoy coming across again in the future with surprise and delight. I did that? Me? Cool!

In grad school, I had a teacher who had a certain delicacy and consistency in her dress, her work habits, the poems she turned out at regular intervals and the books assembled from those poems. She wore the same earrings every day to class, so I couldn’t really imagine her wearing any other. One day in her office hours, she burst out with some passion, saying, “Pearl, I can see that you have this image of what isn’t on the page, and you get all — well, fucked up — about it, so you can’t see what is already on the page and working.” She diagnosed me as a “seasonal” poet, and forgave me for not writing consistently, in the same place for the same amount of time with the same special pen every day. In other words, she urged me to accept what was and what is about the way I do things, and I find myself today urging others to do the same.

I’d love to have a moral to this tale of Reading Realizations, and if I did, it would sound a lot like my teacher’s: Don’t get all fucked up about how and what you’re not doing. Do something, and then do something else, and eventually, you’ll be in a different time and place, learning new things and doing things differently.

That’s what I’m doing, and I found a way to make it work for me. With special pillows, but no special pen.